Soldier’s

‘my dear Fannye’ letter Detailed

look at Fort Custer life

returns here after 110 years

Bighorn County News June 24, 2004 No.25 Vol.97 By Carl Reickmann

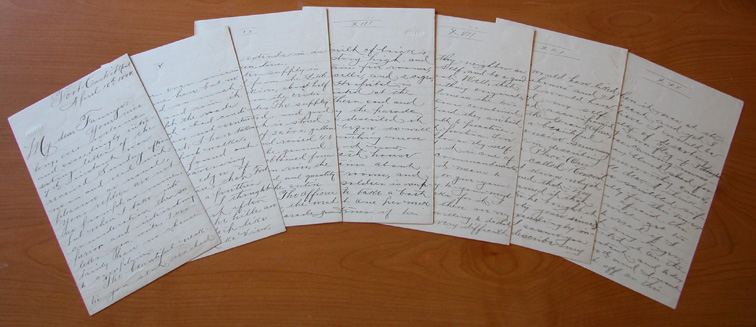

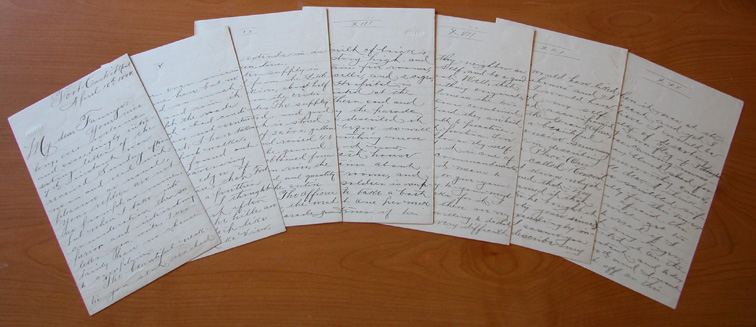

After 110 years, a lonely soldier’s philosophical,

descriptive and opinionated letter to “my dear Fannye” has returned to the

Fort Custer country from which it was mailed in April 1894.

With it, at least until research wins out, comes a mystery.

For without the mailing envelope, the identities of Fanny and her beloved

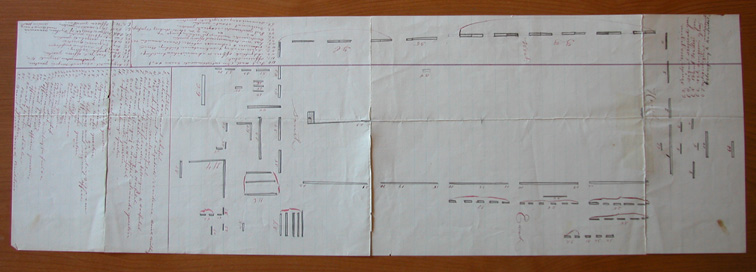

Charles M. are shrouded in those proverbial mists of time. But also with it comes Charles’ fabulous hand drawn layout

of Fort Custer, with descriptive legend of particular buildings, enclosed with

his letter so that Fanny could see his daily surroundings.

And along with his thoughts on political parties, imperialism,

patriotism, operas and his personal devotion to Fannye, his letter describes the

fort and his life. Moreover, it

offers proof of how some things seem never to change, and even injects a point

of view that reoccurs in each war and is part of the current debate about the

conflict in Iraq. “I have always

had a desire to be in a battle when it was at its fiercest, and yet I believe I

would be guilty of deserting my own Flag if I thought it was causing unnecessary

blood-shed for an unworthy cause,” Charles reflects at one point.

Chris Kortlander, director of the Custer Battlefield Museum at Garryowen,

who says he wanted to bring it back to where its historical impact is most

appreciated, purchased the letter and layout via eBay.

Although general publication of contents of such an individual document

tends to devalue its worth, “because everyone has access to the

information,” Kortlander says he wishes to share details with residents local

to the fort that once set on the high bluff on the edge of what became Hardin at

the confluence of the Bighorn and the Little Bighorn rivers.

Actually, Charles was sitting in the lap of luxury, as frontier outposts

go, for Fort Custer and twin Fort Keogh (near Miles City) were the 1877 out

growths of the massacre of Lt. Col. George Custer and his troops, and were well

fashioned and supplied. As Gary W Zowada, former director of Bighorn County

Historical Museum, wrote years ago: “(Fort Custer) was a million-dollar

cavalry post where 500 to 700 men were stationed.

It came to be known as the finest cavalry post in the world and was

visited by both French and German military officers.

Charles does not describe his rank or role at the fort, but his

descriptive abilities could suggest some experience at engineering or

construction: “It stand on a

tableland about 175 feet above the level of these streams in latitude 45

degrees, 43’, 45” north and longitude 107, 31’ west, with an elevation of

nearly 3,238 feet. It lies about 32

miles south from the nearest point of the route of the Northern Pacific R.R. as

it runs along the Yellowstone River and about 15 miles north of the National

Cemetery on the site of the Custer Battlefield.

“The soil, which is said to be composed of alluvial clay is impervious

and tenacious, retaining water on the surface until dried by evaporation.

The climate is marked by extreme of cold in winter and heat in summer.”

Charles moves to the post itself, situated at center of the military’s

reserve in the midst of the Crow Reservation:

“The parade ground is rectangular in shape, the space enclosed in

buildings being 350 yards by 630 yards. On

the West, a few yards beyond the officer’s quarters, steep bluffs rise,

almost perpendicular from the bed of the Bighorn River.

On the East, about a quarter mile in the rear of the barracks, bluffs

less steep rise from the Little Bighorn. These

bluffs meet to the Northeast of the post. To

the South, the elevated plateau extends in an unbroken line.

“The water supply is obtained from the Little Bighorn River, about half

a mile from the center of the parade. The

supply is limited and good in quality; it is stored in a 20,000-gallon capacity

and raised 43 feet above the ground. Our

ice is obtained from the Bighorn River; the quality is good and abundant for the

entire hot weather. “The officers

quarters are on the west side of the parade ground and consist of eleven fairly

constructed wooden buildings, one and a half story, about two feet above the

ground with porches across the front. The

roofs are hip or gambrel with eaves on a level with the second floor.

Each building, except that for the commanding officer, contains two sets

of officer’s quarters. Each set

of quarters contains three rooms, 15’9 x 16’6” x 16’6” and 12’3” x

20’4” with kitchen 12’10 x 12’10; kitchen pantry and dish closet on

first 10” compose the second floor. The

hall is 6’6” wide by 32’4” long. The

barracks for the men are each one story...being 24’ x 23’.

Twenty-five feet in rear of each barracks and parallel with it is a

building 24’ x 126’ connected with the main building by the center from the

front to rear forming two sets of barracks.

“The main building contains the dormitories, first sergeants room and

storeroom. The back buildings form

the Kitchen and Mess Hall. The

wings connecting the two buildings are divided into halls 9’ x 25’, in which

are located the washrooms for the men. The

dormitories are sufficiently large enough to allow each man about 900 cubic feet

of air space. The post guardhouse

is built of brick, one story high and contains five rooms, six cells and two

cages. The hospital is situated at

the northern end and facing the parade.”

His “exceedingly poor” fort layout describes more.

(“If you would hunt the world over, you couldn’t find any men who are

as bad a draughtsman as I am.”) Besides

a number of supplementary outbuildings and adjunct structures, the post

supported a schoolhouse and chapel (with residence for chaplain), carpentry and

laboratory shops, “ dead house belong to hospital,” post exchanges for

various ranks, gymnasium, library, and reading room, post office and signal

office, laundries, blacksmith shop, quartermaster building, guard house, opera

dance hall, officers club, administration building, commissaries, ordnance

storage, vehicle-forage storage, photograph gallery, civilian-employee hotel,

barns, stables, bandstand, fuel storage, union hall for fraternal groups, and

various special quarters for particular roles and ranks.

Charles even addresses sanitation, calling the posts condition good, with

good drainage and policing of the grounds and a 20-room bathhouse. “Each soldier is supposed to take a bath at least one per

week and oftener if he desires,” he explains.

Additionally, he pronounces as good the men’s clothing, and he finds

food and water as and abundant. “And

with all their facilities and conveniences, I would willingly forfeit six months

salary to get back East again, where I would have some place to go at nights and

on Sundays, etc.,” he adds. “The

only way I can kill the time is by reading and playing cards.

I have been out to several Whisk parties lately.

Can you plat Whisk? It’s

my favorite game, and if I am playing with good Whisk players, I can play nearly

all night long without getting sleepy.” The

soldier talks about planning a long horse back ride over the Crow Reservation

since he arrived but not venturing out with much snow or rain affecting roads.

In short walks, however, he finds the fort area “a prettier place then

I thought it was just after arriving.” Charles

muses about seeing Fannye, while ruing the cost of a short furlough, as he

thanks her for a “beautiful ‘neck-tie’” she sent.

“I shall put it away in my treasure box, and when I come to see you, I

will wear it,” he assures her. “I

wish I could come see you this summer, but I am afraid that is impossible, as I

have been assigned to duty here until June 1895, unless I purchase my discharge

or something turns up in the mean time…, although I may be sent away from here

to fill a vacancy somewhere else. I

shall certainly try to get away anyhow, not that I dislike this post as much as

I did when I first arrived, but that I may have a better opportunity of visiting

you.” He notes he could get a

10-20-dy furlough and feels disposed to apply for one.

“(B)ut it would be inconsistent and insensible in me to go to the great

expense of paying my transportation from here to civilization and return for

only a few days recreation,” he poses. “Don’t

you think so? But in June 1895, I

can get three months furlough and the discharge at the expiration of my

furlough, if desired. Don’t you think it would be best for me to wait until

then? Thirteen months!!

It seems like a long time, but time passes swiftly by, and it will get

past ere we know it.” Fannye and Charles apparently had a running political debate,

not unlike one might have today, for he quotes a line (“Love thy neighbor as

thy self and be good democrat.”) apparently from Fannye’s prior letter to

him and finds linkage of the two subjects rather original. “I am afraid both are too difficult to practice,” he

writes. “(Although the) first

portion…is one of the holy commandments, to practice it means to relinquish or

give your last penny to your neighbor if he asks for it.

I am afraid there are very few of us willing to do that.

“It is also very difficult to be a good democrat because you would be

all above if you undertook it. Good democrats used to be the subject of free

trade and Tariff Reform; in the question probably there are as good and as many

true democrats as today as there ever was.

“ Politics to me is the same as religion is to you; i.e., any

particular one is cannot be confined to. I

have stated my objections to back the democratic and the republican parties; the

Populist parties are too bigoted and narrow-minded for me.

I guess I am too hard to suit. I

thought that ere this you would have been trying your argumentative flowers to

win me over in the Democratic side of the house.”

Charles has an interesting take on operatic music, actually not that

impractical. “Do I appreciate

operatic music?” he responds. “Yes,

and still I do not care to go to operas. I

am exceedingly fond of music, but I never went to an opera in my life that I did

not get so tired of it before it was over that I wished I was home or somewhere

else. “They generally begin

shortly after 8 o’clock, an for about an hour or so, I enjoy both the focal

and instrumental part about as well as the next one, but before eleven o’clock

it gets too monotonous to me – comedies, tragedies or dramatical plays.

Of course, there are some operas that I like; probably I would have liked

“ ‘Tannhauser,’ and I know I would have enjoyed myself if I had

accompanied you to the Grand Opera.” Fannye

had also apparently had described her family’s home somewhere back East,

“Haddon Place.” Charles notes he has no idea why this father named their

Virginia home “concord” when he bought it some forty years prior and offers

to describe it sometime to Fannye. Still

with the letter and fort layout is an enclosed piece of an envelope with one of

the MacGregor coats of arm stamped into it.

It seem possible from Charles’ letter, although not conclusive, that he

may have brought up the subject because it was the same as or similar to his

last name. A postscript to his

letter is ended with the initials C.M. “The

old ‘MacGregor’ clan of Scotland has three coats of arms, and this is one of

them,” he tells Fannye. “All of

our books in the library have this insignia stamped in them, for identification.

If he is talking about the posts library, rather then a family one back

home in Virginia, then it’s a further mystery why the post books would have

been stamped with a MacGregor coat of arms.

Charles refers to reading “Scottish Chiefs” first when he was 10 or

12 years old. “Writing of that

kind always leaves great impressions on children’s minds ever afterward, and

that is one of the reasons I have never liked England, although she has some of

the noblest and best people of the civilized world,” he relates.

“some of the best friends I have are English, and yet England herself I

dislike more than any other civilized country in the world for the way she

treated Scotland, the way she was treating the United States until the war of

’76 and, in fact, the way she treats Ireland and every other small country

that she can.” Then, he allows

the axiom about everything being fair in love and war and that England is

ambitious. “I admire any country

for being ambitious, but I think that an ambitious country should resort to

other means of advancing its interests than by causing bloodshed and Unnecessary

suffering,” he asserts. “England

always reminds me of a big dog jumping on a little one and whipping it, just

because it could.” Then, he

offers his patriotic assessment about wanting to be in the thick of a fight but

having second thoughts if he figured a battle “was causing unnecessary

bloodshed for an unworthy cause.” Research

may never reveal if Fannye and Charles spent a lifetime together, but any

breakdown in the relationship would not have been for any lack of expression

concerning her letters. “Your

nice long, ever welcome and exceedingly interesting letter of the 7th

instant was received Sunday afternoon and read with pleasure as usual,”

Charles says lovingly. “Your

replies are not as prompt as mine, but when I take into consideration the

superior and interesting letter you write, I certainly have no chance to

complain.

And along with his thoughts on political parties, imperialism,

patriotism, operas and his personal devotion to Fannye, his letter describes the

fort and his life. Moreover, it

offers proof of how some things seem never to change, and even injects a point

of view that reoccurs in each war and is part of the current debate about the

conflict in Iraq. “I have always

had a desire to be in a battle when it was at its fiercest, and yet I believe I

would be guilty of deserting my own Flag if I thought it was causing unnecessary

blood-shed for an unworthy cause,” Charles reflects at one point.

Chris Kortlander, director of the Custer Battlefield Museum at Garryowen,

who says he wanted to bring it back to where its historical impact is most

appreciated, purchased the letter and layout via eBay.

Although general publication of contents of such an individual document

tends to devalue its worth, “because everyone has access to the

information,” Kortlander says he wishes to share details with residents local

to the fort that once set on the high bluff on the edge of what became Hardin at

the confluence of the Bighorn and the Little Bighorn rivers.

Actually, Charles was sitting in the lap of luxury, as frontier outposts

go, for Fort Custer and twin Fort Keogh (near Miles City) were the 1877 out

growths of the massacre of Lt. Col. George Custer and his troops, and were well

fashioned and supplied. As Gary W Zowada, former director of Bighorn County

Historical Museum, wrote years ago: “(Fort Custer) was a million-dollar

cavalry post where 500 to 700 men were stationed.

It came to be known as the finest cavalry post in the world and was

visited by both French and German military officers.

Charles does not describe his rank or role at the fort, but his

descriptive abilities could suggest some experience at engineering or

construction: “It stand on a

tableland about 175 feet above the level of these streams in latitude 45

degrees, 43’, 45” north and longitude 107, 31’ west, with an elevation of

nearly 3,238 feet. It lies about 32

miles south from the nearest point of the route of the Northern Pacific R.R. as

it runs along the Yellowstone River and about 15 miles north of the National

Cemetery on the site of the Custer Battlefield.

“The soil, which is said to be composed of alluvial clay is impervious

and tenacious, retaining water on the surface until dried by evaporation.

The climate is marked by extreme of cold in winter and heat in summer.”

Charles moves to the post itself, situated at center of the military’s

reserve in the midst of the Crow Reservation:

“The parade ground is rectangular in shape, the space enclosed in

buildings being 350 yards by 630 yards. On

the West, a few yards beyond the officer’s quarters, steep bluffs rise,

almost perpendicular from the bed of the Bighorn River.

On the East, about a quarter mile in the rear of the barracks, bluffs

less steep rise from the Little Bighorn. These

bluffs meet to the Northeast of the post. To

the South, the elevated plateau extends in an unbroken line.

“The water supply is obtained from the Little Bighorn River, about half

a mile from the center of the parade. The

supply is limited and good in quality; it is stored in a 20,000-gallon capacity

and raised 43 feet above the ground. Our

ice is obtained from the Bighorn River; the quality is good and abundant for the

entire hot weather. “The officers

quarters are on the west side of the parade ground and consist of eleven fairly

constructed wooden buildings, one and a half story, about two feet above the

ground with porches across the front. The

roofs are hip or gambrel with eaves on a level with the second floor.

Each building, except that for the commanding officer, contains two sets

of officer’s quarters. Each set

of quarters contains three rooms, 15’9 x 16’6” x 16’6” and 12’3” x

20’4” with kitchen 12’10 x 12’10; kitchen pantry and dish closet on

first 10” compose the second floor. The

hall is 6’6” wide by 32’4” long. The

barracks for the men are each one story...being 24’ x 23’.

Twenty-five feet in rear of each barracks and parallel with it is a

building 24’ x 126’ connected with the main building by the center from the

front to rear forming two sets of barracks.

“The main building contains the dormitories, first sergeants room and

storeroom. The back buildings form

the Kitchen and Mess Hall. The

wings connecting the two buildings are divided into halls 9’ x 25’, in which

are located the washrooms for the men. The

dormitories are sufficiently large enough to allow each man about 900 cubic feet

of air space. The post guardhouse

is built of brick, one story high and contains five rooms, six cells and two

cages. The hospital is situated at

the northern end and facing the parade.”

His “exceedingly poor” fort layout describes more.

(“If you would hunt the world over, you couldn’t find any men who are

as bad a draughtsman as I am.”) Besides

a number of supplementary outbuildings and adjunct structures, the post

supported a schoolhouse and chapel (with residence for chaplain), carpentry and

laboratory shops, “ dead house belong to hospital,” post exchanges for

various ranks, gymnasium, library, and reading room, post office and signal

office, laundries, blacksmith shop, quartermaster building, guard house, opera

dance hall, officers club, administration building, commissaries, ordnance

storage, vehicle-forage storage, photograph gallery, civilian-employee hotel,

barns, stables, bandstand, fuel storage, union hall for fraternal groups, and

various special quarters for particular roles and ranks.

Charles even addresses sanitation, calling the posts condition good, with

good drainage and policing of the grounds and a 20-room bathhouse. “Each soldier is supposed to take a bath at least one per

week and oftener if he desires,” he explains.

Additionally, he pronounces as good the men’s clothing, and he finds

food and water as and abundant. “And

with all their facilities and conveniences, I would willingly forfeit six months

salary to get back East again, where I would have some place to go at nights and

on Sundays, etc.,” he adds. “The

only way I can kill the time is by reading and playing cards.

I have been out to several Whisk parties lately.

Can you plat Whisk? It’s

my favorite game, and if I am playing with good Whisk players, I can play nearly

all night long without getting sleepy.” The

soldier talks about planning a long horse back ride over the Crow Reservation

since he arrived but not venturing out with much snow or rain affecting roads.

In short walks, however, he finds the fort area “a prettier place then

I thought it was just after arriving.” Charles

muses about seeing Fannye, while ruing the cost of a short furlough, as he

thanks her for a “beautiful ‘neck-tie’” she sent.

“I shall put it away in my treasure box, and when I come to see you, I

will wear it,” he assures her. “I

wish I could come see you this summer, but I am afraid that is impossible, as I

have been assigned to duty here until June 1895, unless I purchase my discharge

or something turns up in the mean time…, although I may be sent away from here

to fill a vacancy somewhere else. I

shall certainly try to get away anyhow, not that I dislike this post as much as

I did when I first arrived, but that I may have a better opportunity of visiting

you.” He notes he could get a

10-20-dy furlough and feels disposed to apply for one.

“(B)ut it would be inconsistent and insensible in me to go to the great

expense of paying my transportation from here to civilization and return for

only a few days recreation,” he poses. “Don’t

you think so? But in June 1895, I

can get three months furlough and the discharge at the expiration of my

furlough, if desired. Don’t you think it would be best for me to wait until

then? Thirteen months!!

It seems like a long time, but time passes swiftly by, and it will get

past ere we know it.” Fannye and Charles apparently had a running political debate,

not unlike one might have today, for he quotes a line (“Love thy neighbor as

thy self and be good democrat.”) apparently from Fannye’s prior letter to

him and finds linkage of the two subjects rather original. “I am afraid both are too difficult to practice,” he

writes. “(Although the) first

portion…is one of the holy commandments, to practice it means to relinquish or

give your last penny to your neighbor if he asks for it.

I am afraid there are very few of us willing to do that.

“It is also very difficult to be a good democrat because you would be

all above if you undertook it. Good democrats used to be the subject of free

trade and Tariff Reform; in the question probably there are as good and as many

true democrats as today as there ever was.

“ Politics to me is the same as religion is to you; i.e., any

particular one is cannot be confined to. I

have stated my objections to back the democratic and the republican parties; the

Populist parties are too bigoted and narrow-minded for me.

I guess I am too hard to suit. I

thought that ere this you would have been trying your argumentative flowers to

win me over in the Democratic side of the house.”

Charles has an interesting take on operatic music, actually not that

impractical. “Do I appreciate

operatic music?” he responds. “Yes,

and still I do not care to go to operas. I

am exceedingly fond of music, but I never went to an opera in my life that I did

not get so tired of it before it was over that I wished I was home or somewhere

else. “They generally begin

shortly after 8 o’clock, an for about an hour or so, I enjoy both the focal

and instrumental part about as well as the next one, but before eleven o’clock

it gets too monotonous to me – comedies, tragedies or dramatical plays.

Of course, there are some operas that I like; probably I would have liked

“ ‘Tannhauser,’ and I know I would have enjoyed myself if I had

accompanied you to the Grand Opera.” Fannye

had also apparently had described her family’s home somewhere back East,

“Haddon Place.” Charles notes he has no idea why this father named their

Virginia home “concord” when he bought it some forty years prior and offers

to describe it sometime to Fannye. Still

with the letter and fort layout is an enclosed piece of an envelope with one of

the MacGregor coats of arm stamped into it.

It seem possible from Charles’ letter, although not conclusive, that he

may have brought up the subject because it was the same as or similar to his

last name. A postscript to his

letter is ended with the initials C.M. “The

old ‘MacGregor’ clan of Scotland has three coats of arms, and this is one of

them,” he tells Fannye. “All of

our books in the library have this insignia stamped in them, for identification.

If he is talking about the posts library, rather then a family one back

home in Virginia, then it’s a further mystery why the post books would have

been stamped with a MacGregor coat of arms.

Charles refers to reading “Scottish Chiefs” first when he was 10 or

12 years old. “Writing of that

kind always leaves great impressions on children’s minds ever afterward, and

that is one of the reasons I have never liked England, although she has some of

the noblest and best people of the civilized world,” he relates.

“some of the best friends I have are English, and yet England herself I

dislike more than any other civilized country in the world for the way she

treated Scotland, the way she was treating the United States until the war of

’76 and, in fact, the way she treats Ireland and every other small country

that she can.” Then, he allows

the axiom about everything being fair in love and war and that England is

ambitious. “I admire any country

for being ambitious, but I think that an ambitious country should resort to

other means of advancing its interests than by causing bloodshed and Unnecessary

suffering,” he asserts. “England

always reminds me of a big dog jumping on a little one and whipping it, just

because it could.” Then, he

offers his patriotic assessment about wanting to be in the thick of a fight but

having second thoughts if he figured a battle “was causing unnecessary

bloodshed for an unworthy cause.” Research

may never reveal if Fannye and Charles spent a lifetime together, but any

breakdown in the relationship would not have been for any lack of expression

concerning her letters. “Your

nice long, ever welcome and exceedingly interesting letter of the 7th

instant was received Sunday afternoon and read with pleasure as usual,”

Charles says lovingly. “Your

replies are not as prompt as mine, but when I take into consideration the

superior and interesting letter you write, I certainly have no chance to

complain.